Upcoming Events at TAUNY

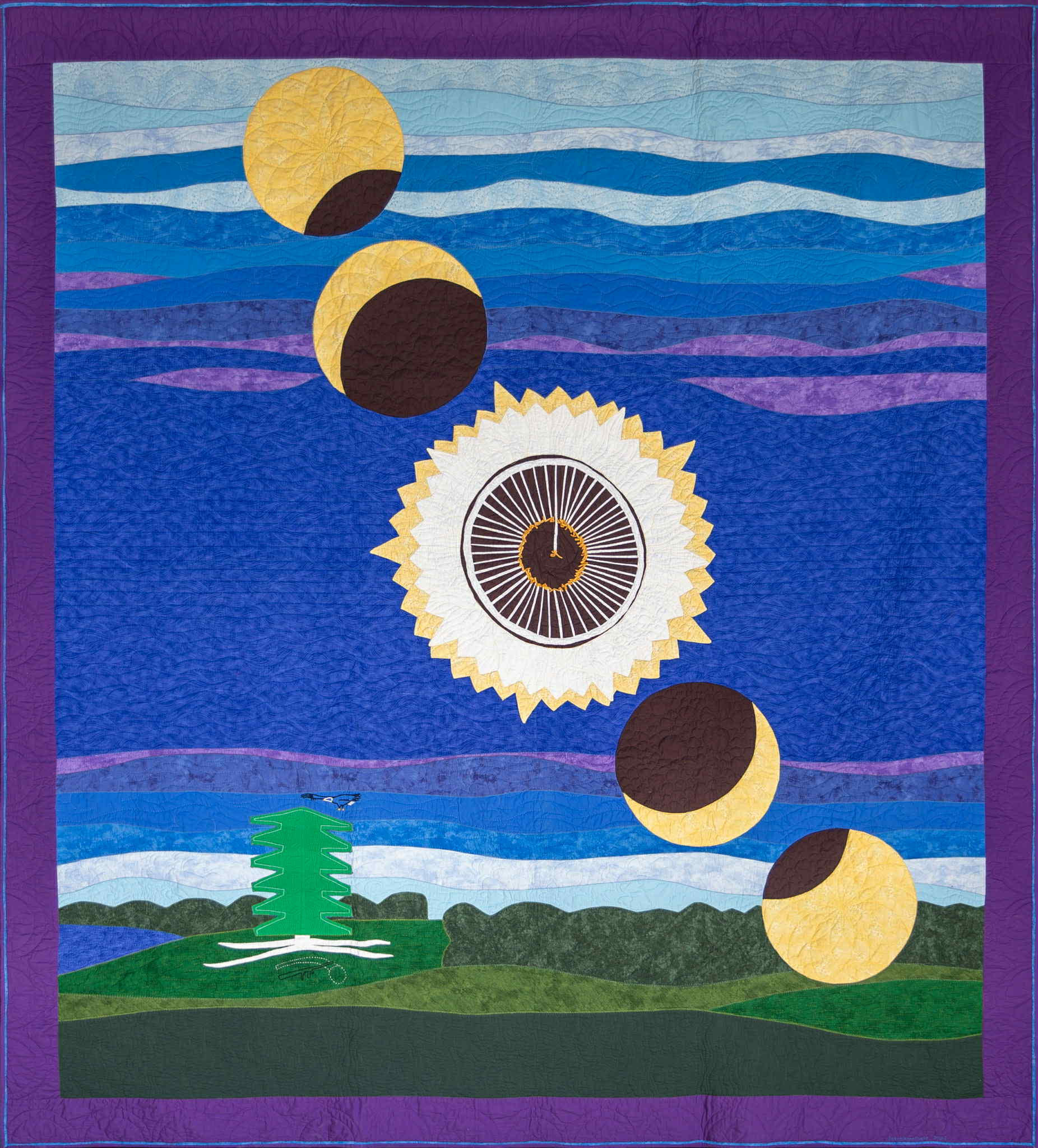

Exhibit: "Legacies – Handing Down Traditional Fiber Arts"

Opening Reception Saturday, August 2nd 1-3 p.m.

The “Legacies” exhibit will focus on how the practices of traditional fiber arts are passed down within families and amongst local artisans. Featuring over 20 artists, and drawing on two fiber arts groups that meet regularly at TAUNY, the exhibit aligns with the organization’s mission to honor living traditions.

Exhibit runs through September 25th, 2025

Exhibition: Mohawk Art & Environmental Stewardship

Opening Reception - Saturday, October 18th

1 - 2 p.m.

TAUNY is proud to partner with the Akwesasne Cultural Center on a exhibit which will be featured at each of their organizations. The project focuses on three traditional art forms (cermaics, regalia & fiber arts (weaving & basketmaking) and the resilence and celebration of the Awkesasne Mohawk and its artists in the face of environmental challenges to their community. Thank you to the Coby Foundation and MidAtlantic Arts for their support of this project.

Exhibit runs through February 14th, 2026

North Country Folk Orchestra

Monday's 9/22 - 10/27, Performance 11/1

5:30-7 p.m., 4-5:30 p.m.

TAUNY Now in its third season, the North Country Folk Orchestra brings together acoustic musicians of all ages to play fiddle and dance tunes enjoyed in Northern New York. Directed by Gretchen Koehler and assisted by Barb Heller, there are six workshop sessions and one final performance for the public. Tuition is $50 for ages 18 and over, and $15 for under 18. This program is made possible with support from Petya Perkins Family Fund and the Corning Foundation.

Figure Drawing

2nd Wednesday's - September - December 2025

To all visual artists, join TAUNY for a series of open nude figure drawing sessions at The Center upstairs boardroom. 9/10, 10/08, 11/12, 12/10. Tickets are $10 and registration is encouraged. Limited to 12 Participants & 18+ only.

Fiddling with Traditions

November 13th & 14th, 2025

TAUNY is proud to present award-winning duo Gretchen Koehler & Daniel Kelley’s original concert & workshop series which pays a multimedia homage to handcrafted traditions in the North Country. Fiddling with Traditions will be brought to Indian River Central Schools on November 13th and Keene Valley Central Schools on 11/14, 2025. Thank you to the Cloudsplitter Foundation and NNYCF’s Car Freshner’s Foundation for their support of this program.

Contra Dance - St Lawrence University

Monday, August 25th 2025

2-3:30 p.m.

As part of TAUNY’s ongoing Arts Education programs, the organization is delighted to host for the second year St. Lawrence University’s first year students for a traditional Contra Dane at The TAUNY Center. As part of SLU’s Backyard Adventures, forty students will learn to dance Contra led by professional caller Beth Robinson and supported by world class fiddler Gretchen Koehler and expert keyboardist Matt Bullwinkle. Special thank you to the Petya Perkins Family Foundation for making this event possible. *Please note, this program is not open to the general public.

THE TAUNY CENTER

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places and part of Canton’s downtown Historic District, The TAUNY Center is an anchor space for local residents, tourists, artists, and artisans. As a central arts and cultural organization, TAUNY attracts thousands of local and regional audiences to experience live music, workshops, exhibits, and to purchase local artwork. The facility is a hub of activity which contributes to the foot traffic in the historic downtown district and generates economic activity, adding to the vibrancy of the region.

CURRENT CAPITAL PROJECT

TAUNY is undertaking the final phase of its capital campaign at its Center to address several deficiencies at the facility. This project includes the addition of an automatic door opener, replacement of all windows, updating the TAUNY sign, awning, doors, and full front facade to be more historically accurate, functional, and which will enhance the streetscape.

FOLKSTORE: NEW & NOTEWORTHY

Folkstore Friday features a new artisan each week whose work is displayed and sold in The TAUNY Center. This week we are featuring the works of Jennifer Sampson, whose plein air oil paintings are now available at The TAUNY Center Folkstore.

#folkstorefriday

ARTS EDUCATION

TAUNY’s Arts Education programs offer a series of educational workshops, residencies, and accompanying performances in traditional art forms for all ages at The TAUNY Center, schools, and other community based organizations in the North Country.

PLACEMAKING - ARCHWAY PROJECT

A new public art project entitled the Archway at Prentice Lane is being planned in partnership with the Village of Canton, which features the installation of a freestanding decorative archway on Main Street. The piece will be made by professional artist James Gonzalez, a metalworker who creates large-scale works which feature distinctive attributes of the areas he serves.

RESEARCH - FOLK STUDIES/ARCHIVES

TAUNY’s presentations of the customs and traditions of the North Country begin with research. Our staff and a network of scholars with whom we work travel around the region to study and document ongoing cultural practices in our communities. Read about our current research projects here.

NEWS & CONNECT - NEWBERRY CAFE - NOW OPEN*

The Newberry cafe is now open Monday, Wednesday, Friday from 10:30 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. and featuring paninis (meat & vegetarian), crepes, quiches (meat & vegetarian), soups, salads and a variety of beverages! Find out about our grant opening and more by clicking the tab below.

FEATURED PRACTICING ARTIST & EDUCATOR: KATE SCHULER

Katherine Schuler is an art educator, woodworker and owner of Schuler Woodworks in Potsdam, NY. In her thirteen years of teaching, Katie has had a variety of experiences and the opportunity to teach students at every grade level. She finds immense joy in the ingenuity of students at every age level and works to facilitate a safe space for them to continue their creative work. As a woodworker, she has been creating pieces for the last decade. Her hope is to share her love for woodworking with others through custom furniture, artworks, jewelry and functional household items.

Support TAUNY

Your support creates direct positive change within the TAUNY community. Every donation, regardless of size, is essential for bringing our programs to life, from educational workshops to performances that highlight New York’s North Country folk culture. By contributing, you help foster an inclusive space that celebrates traditions, supports artists, and strengthens community bonds. Together, we can ensure our cultural identity and practices thrive for future generations.