Featured & Upcoming Events

Fiberistas 2026 Exhibition: "Tribute to TAUNY"

Opening Reception: Saturday, March 7th, 12 p.m.

TAUNY The Fiberistas annual display for 2026 is entitled “Tribute to TAUNY” and features a series of quilts that are a testament to the TAUNY Center and traditional art forms in Northern New York. Join us for a free opening reception on Saturday, March 7th at 12 p.m. complete with a Q&A session with participating artists, and refreshments.

40th Anniversary Kickoff!

January - December, 2026

TAUNY kicked off its 40th Anniversary with a successful celebration & North Country Living Traditions Awards ceremony, which took place on Friday, January 16th at The TAUNY Center. Congratulations to this years recipient of the award, the Atkinson Family Band from Harrisville, New York. A documentary made by Filmmaker & Folklorist Clara Riedlinger about these artists was premiered at the event. Thank you to the Sweetgrass Foundation and Northern New York Community Foundation’s Thompson-Weatherup Family Charitable Foundation (T-WFCF) for their generous grants in support of this program.

Sugaring Off Party

Saturday, March 21st 2-4 p.m.

TAUNY

People of all ages are invited to a musical and dance celebration of maple sugaring season! This free interactive concert and family oriented dance is presented by the Madstop Fiddlers of Potsdam, a multigenerational group of fiddlers under the direction of Gretchen Koehler. Musical concert is immediately followed by a community dance, and Hurlbut Farms will be back with their special treats, Sugar on Snow!

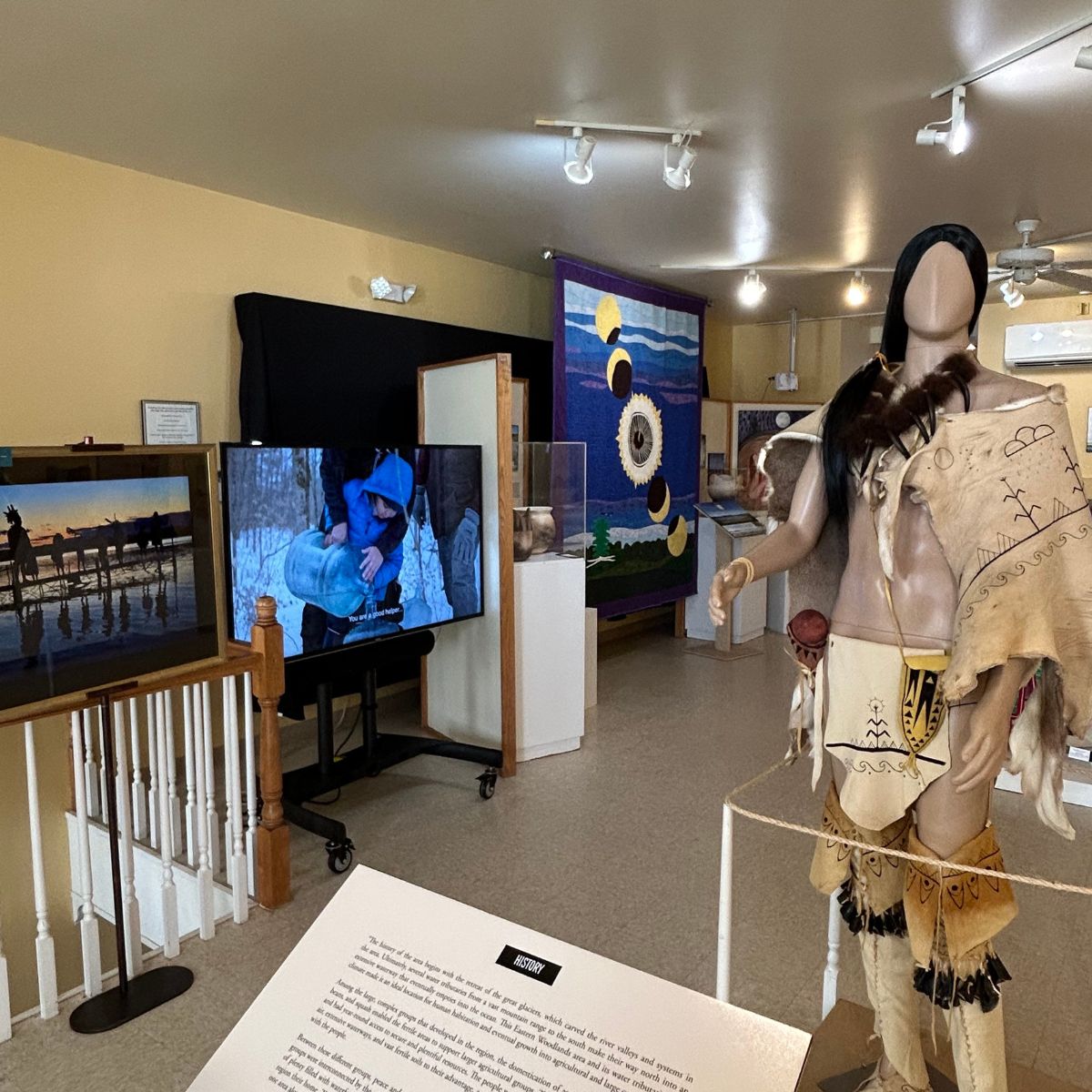

Traveling Exhibition: Mohawk Arts & Environmental Stewardship

Opens at the Akwesasne Cultural Center - March 20th, 5 p.m.

TAUNY’s latest exhibition “Threads of Connection: Mohwak Arts & Environmental Stewardship” is hitting the road! A celebration of the artisan work and practices of ten Akwesasne Mohawk artists, examined in the context of their interrelationships and ongoing challenges with the environment. This program is made possible with support from the New York State Council on the Arts, with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature, the Coby Foundation, and SeaComm Federal Credit Union. This project is also supported by the Midatlantic Folk & Traditional Arts – Community Projects program.

Akwesasne Cultural Center Opening Reception Friday, March 20th 5 p.m. & runs through July 17th

Figure Drawing Guild

Wednesday, March 11th 3-5 p.m.

Studio artists join us for our monthly (every second Wednesdsay) Figure Drawing Guild at The TAUNY Center in partnership with the St. Lawrence Arts Council & Frederic Remington Art Museum. In a safe and welcoming environment, live models pose for artists to render the human body. Registration is required through the St. Lawrence Arts Council and there is seating for 12. 18+ only

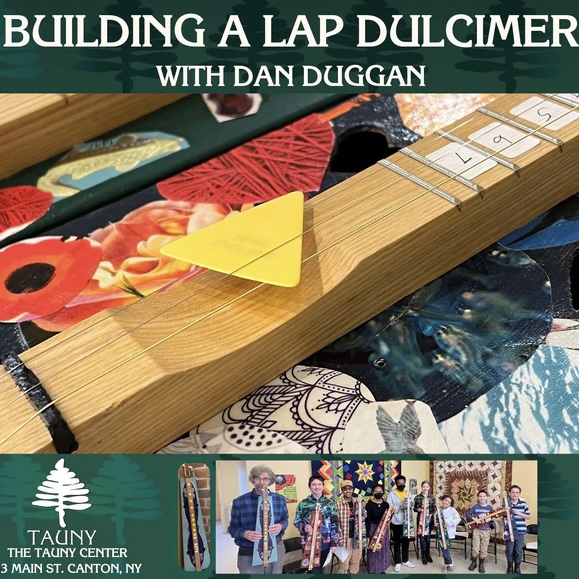

Lap Dulcimer Workshop Series - Youth

Saturdays: March 7th,14th & 21st

Whether they are budding musicians or have never picked up an instrument before, the lap dulcimer is a fun, easy way for young people to make music together. This three part series is led by TAUNY teaching artist Dan Duggan, a master dulcimer player has worked in schools throughout the Northeast for over 30 years. He has put together a multi-day workshop to guide participants through decorating, building and learning to play their own lap dulcimer! The workshop culminates in a final performance at the Sugaring Off Party at The TAUNY Center on 3/21.

$50 for all three sessions!

THE TAUNY CENTER

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places and part of Canton’s downtown Historic District, The TAUNY Center is an anchor space for local residents, tourists, artists, and artisans. As a central arts and cultural organization, TAUNY attracts thousands of local and regional audiences to experience live music, workshops, exhibits, and to purchase local artwork. The facility is a hub of activity which contributes to the foot traffic in the historic downtown district and generates economic activity, adding to the vibrancy of the region.

CURRENT CAPITAL PROJECT

TAUNY is undertaking the final phase of its capital campaign at its Center to address several deficiencies at the facility. This project includes the addition of an automatic door opener, replacement of all windows, updating the TAUNY sign, awning, doors, and full front facade to be more historically accurate, functional, and which will enhance the streetscape.

FOLKSTORE: NEW & NOTEWORTHY

Folkstore Friday features a new artisan each week whose work is displayed and sold in The TAUNY Center. This week we are featuring the works of Jennifer Sampson, whose plein air oil paintings are now available at The TAUNY Center Folkstore.

#folkstorefriday

ARTS EDUCATION

TAUNY’s Arts Education programs offer a series of educational workshops, residencies, and accompanying performances in traditional art forms for all ages at The TAUNY Center, schools, and other community based organizations in the North Country.

PLACEMAKING - ARCHWAY PROJECT

A new public art project entitled the Archway at Prentice Lane is being planned in partnership with the Village of Canton, which features the installation of a freestanding decorative archway on Main Street. The piece will be made by professional artist James Gonzalez, a metalworker who creates large-scale works which feature distinctive attributes of the areas he serves.

RESEARCH - FOLK STUDIES/ARCHIVES

TAUNY’s presentations of the customs and traditions of the North Country begin with research. Our staff and a network of scholars with whom we work travel around the region to study and document ongoing cultural practices in our communities. Read about our current research projects here.

NEWS & CONNECT - NEWBERRY CAFE - NOW OPEN*

The Newberry cafe is now open Monday, Wednesday, Friday from 10:30 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. and featuring paninis (meat & vegetarian), crepes, quiches (meat & vegetarian), soups, salads and a variety of beverages! Find out about our grant opening and more by clicking the tab below.

FEATURED PRACTICING ARTIST & EDUCATOR: KATE SCHULER

Katherine Schuler is an art educator, woodworker and owner of Schuler Woodworks in Potsdam, NY. In her thirteen years of teaching, Katie has had a variety of experiences and the opportunity to teach students at every grade level. She finds immense joy in the ingenuity of students at every age level and works to facilitate a safe space for them to continue their creative work. As a woodworker, she has been creating pieces for the last decade. Her hope is to share her love for woodworking with others through custom furniture, artworks, jewelry and functional household items.

Support TAUNY

Your support creates direct positive change within the TAUNY community. Every donation, regardless of size, is essential for bringing our programs to life, from educational workshops to performances that highlight New York’s North Country folk culture. By contributing, you help foster an inclusive space that celebrates traditions, supports artists, and strengthens community bonds. Together, we can ensure our cultural identity and practices thrive for future generations.